|

Case Report

Static bone cavity of the mandible: A case report

1 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250012, China

Address correspondence to:

Xianguang Liu

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250012,

China

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100040Z07XL2022

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Liu X, Xu W, Wang X. Static bone cavity of the mandible: A case report. J Case Rep Images Dent 2022;8:100040Z07XL2022.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Stafne bone cavity is a rare structural abnormality. It is often accidentally discovered during radiographic examination as clinical symptoms are usually absent.

Case Report: We report a case of mandibular Stafne bone cavity in a 38-year-old man with typical imaging features. It manifests on imaging as a defect or depression on the lingual side of the mandible; it appears round or oval with a clear boundary and is located below the mandibular canal and above the lower border of the mandible. After two years of follow-up, no changes were found in the bone cavity.

Conclusion: Static bone cavity (SBC) of the mandible belongs to developmental malformation, and there will be no progressive progress of the bone cavity. Its characteristic imaging manifestations are conducive to the diagnosis of the disease. This case can enhance our understanding of the SBC of the mandible and help dentists better diagnose this lesion and avoid over treatment.

Keywords: Mandible, Stafne bone cavity, Static bone cavity, Submandibular gland

Introduction

Static bone cavity (SBC), also known as Stafne bone cavity was first described by Edward Stafne in 1942 as an asymptomatic unilateral cortical invagination in the lingual mandible or a “bone cavity near mandibular angle” [1]. The etiology of the disease is unknown, and hypertrophy of the salivary glands is thought to be the main cause. Its occurrence is mostly unilateral, however, bilateral cases have also been reported [2]. Clinically, it is very rare and are cortical defects near the angle of the mandible below the mandibular canal with a clear boundary. It is usually an incidental finding and represents a depression in the medial aspect of the mandible filled by part of the submandibular gland or adjacent fat [3]. This article reports a case of SBC, describes its clinical features and imaging findings, reviews relevant literature, and provides guidance for accurate clinical diagnosis.

Case Report

Medical records: A well-defined low-density shadow was detected on the left posterior mandibular body during tomographic examination for bilateral impacted mandibular teeth in a 38-year-old man. The patient had no significant medical history or history of trauma. The patient visited the hospital for the first time in July 2019 and took CBCT examination. The diagnosis was considered as SBC. He returned to the hospital in August 2021 and took Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) examination.

Physical examination: The facial profile of the patient was symmetrical. The patient reported no pain or other discomfort in the left mandible area and there was no lower lip numbness. There was no tenderness on palpation of the buccal and lingual sides of the left posterior mandible and in the region of the bone defect on the lingual side. Erythema and edema of the mucosa were absent.

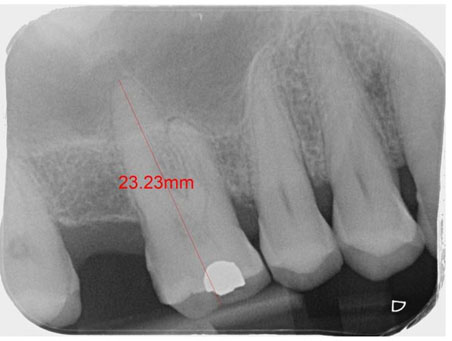

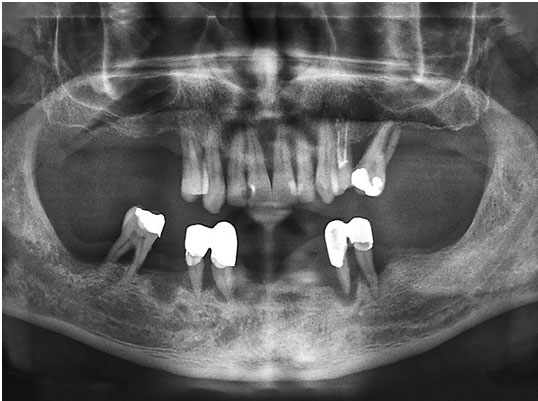

Imaging findings: Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) showed an oval low-density shadow between the mandibular canal and the lower border of the mandible, distal to tooth 38 (Figure 1). The lesion had a clear boundary and linear high-density edges. The CBCT cross-section showed a well-defined lingual defect in the left posterior mandible with only a thin layer of cortical bone on the buccal side and soft tissue shadow within the lesion (Figure 2A); the sagittal view revealed a round low-density shadow with a clear boundary, surrounded by bone walls, in the left mandible. The coronal view showed a well-defined bone cavity in the lingual mandible, adjacent to the mandibular canal; the lower border of the mandible was continuous, and the buccal cortical bone was thin without fenestration (Figure 2B). Because of the patient’s characteristic imaging findings, SBC was diagnosed and no surgical treatment was performed. After two years of follow-up imaging observation, no further development of mandibular bone cavity was found (Figure 3).

Discussion

Stafne bone cavity is a rare structural abnormality of the mandible, also described as a lingual depression of mandible, developmental salivary gland defect, Stafne defect, latent bone cyst, and idiopathic bone cavity. At present, the etiology of SBC is not clear. Some studies accept the theory of congenital malformations because submandibular gland tissue is often found in the bone cavity during surgical exploration. It is believed that the salivary gland tissue is embedded in the mandible during the development or ossification of the mandible, which can also explain the existence of thin lingual cortical bone [4]. Another view is that the asymptomatic bone cavity is caused by the compression of the salivary glands, especially the submandibular gland on the mandible, which results in defects of the lingual cortex of the mandible [5]. In some cases, SBC is filled with adipose tissue, blood vessels, and other structures, which is considered to be caused by lipoma, or vascular lesions [6]. He et al. [7] have reported a case of SBC containing simple lymph node tissue, and Alaettin et al. [8] described a case of SBC present in both anterior and posterior parts of the mandibular body. Aps et al. observed that compression of the submandibular gland tissue against the lingual cortex resulted in the posterior type of SBC, and the compression of the sublingual gland against the mandible caused the anterior type of SBC [9]. According to Sisman et al. [10] SBC can contain salivary gland, muscle, lymphatic, vascular, adipose, or other connective tissues.

The incidence of SBC is generally low but varies across reports. A study by Assaf et al. [2] suggests that the incidence of SBC varies between 0.1% and 0.48%, and the incidence among men, especially those aged 40–70 years, is significantly higher than among women. Aps et al. [9] reported that the incidence of SBC is 0.58%, that of anterior SBC is 0.04% and of posterior SBC 0.54%, with a male to female ratio of 13:1. The onset age ranges from 32 to 82 years, with an average age of 58.14 years. Munevvero?lu et al. [11] reported that the incidence of anterior SBC is 0.003% and that of posterior SBC is 0.081%, with a male to female ratio of 25:4; the onset age ranges from 18 to 77 years, with the average age of 49.6 years. Although the youngest reported patient of SBC was an 11-year-old boy [12], it takes decades for the development of SBC and its detection on radiographs [13]. Probst et al. [14] reported that progressive development of SBC without clinical symptoms was identified by observing two curved faults of the same patient at an interval of 7 years, which also explains the high incidence in the aged. In fact, the actual incidence of SBC may be higher than reported because it is difficult to detect without radiographic examination if the patient does not have abnormal clinical symptoms. Static bone cavity is usually an asymptomatic lesion that is accidentally discovered during imaging examination. In rare cases, symptoms such as pain, bleeding, or fistula may occur [15].

Static bone cavity is easily misdiagnosed as a benign lesion due to its location in the jaw and sometimes as a neurolemmoma when it is located close to the mandibular canal. In addition, it should be differentiated from giant cell granuloma of the jaw, keratocystic odontogenic tumor, ameloblastoma, and odontogenic cyst. Maxillofacial surgeons usually make preliminary judgment on SBC through curved tomography, on which the lesion manifests as an oval, clear, low-density shadow below the mandibular canal and above the lower border of the mandible. Anterior SBCs are mostly located at the root of the canine and the first premolar, due to which they can be easily misdiagnosed as an odontogenic tumor. Three-dimensional imaging, such as CBCT, has a strong diagnostic significance. The diameter of the lesion is usually 1–3 cm. It is mostly located between the first molar and the mandibular angle, showing uniform density of soft tissue shadows. The three-dimensional positional relationship obtained through CBCT is important for differential diagnosis of SBC [16]. Salivary gland tissue, adipose tissue, connective tissue, and lymphatic tissue, among others, may be present in an SBC. Relevant information about soft tissue can be obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using high resolution for soft tissue and T1, T2-weighted sequencing, which is more conducive to the diagnosis of SBC. Salivary gland angiography is an effective method to identify if gland tissue is present in an SBC, except no salivary glands contain SBC or anterior SBC cases, whose sublingual gland duct is small, and thus imaging is difficult [13],[17],[18]. Salivary gland angiography can be used as a supplement to the diagnosis of SBC. Clinically, once an SBC is suspected, regular imaging follow-up is recommended. No surgical treatment is required in most cases, and intra-osseous infection or malignant transformation is rare; biopsy or surgical exploration is performed if malignancy is suspected [18].

Conclusion

Static bone cavity is a rare benign mandible defect that generally does not cause pathological changes. Most cases are asymptomatic and without progression. A typical SBC can be definitively diagnosed by radiographic examinations, such as CT or MRI. Periodic imaging is generally preferable to surgical treatment in order to avoid excessively invasive management.

REFERENCE

1.

Stafne EC. Bone cavities situated near the angle of the mandible. The Journal of the American Dental Association 1942;29(17):1969–72. [CrossRef]

2.

Assaf AT, Solaty M, Zrnc TA, et al. Prevalence of Stafne’s bone cavity – Retrospective analysis of 14,005 panoramic views. In Vivo 2014;28(6):1159–64.

[Pubmed]

3.

Liang J, Deng Z, Gao H. Stafne’s bone defect: A case report and review of literatures. Ann Transl Med 2019;7(16):399. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

de Courten A, Küffer R, Samson J, et al. Anterior lingual mandibular salivary gland defect (Stafne defect) presenting as a residual cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;94(4):460–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Chaudhry A. Stafne’s bone defect with bicortical perforation: A need for modified classification system. Oral Radiol 2021;37(1):130–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Minowa K, Inoue N, Sawamura T, Matsuda A, Totsuka Y, Nakamura M. Evaluation of static bone cavities with CT and MRI. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003;32(1):2–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

He J, Wang J, Hu Y, Liu W. Diagnosis and management of Stafne bone cavity with emphasis on unusual contents and location. J Dent Sci 2019;14(4):435–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

9.

Aps JKM, Koelmeyer N, Yaqub C. Stafne’s bone cyst revisited and renamed: The benign mandibular concavity. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2020;49(4):20190475. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Sisman Y, Miloglu O, Sekerci AE, Yilmaz AB, Demirtas O, Tokmak TT. Radiographic evaluation on prevalence of Stafne bone defect: A study from two centres in Turkey. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012;41(2):152–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Münevveroğlu AP, Aydin KC. Stafne bone defect: Report of two cases. Case Rep Dent 2012;2012:654839. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Koç A, Eroğlu CN, Bilgili E. Assessment of prevalence and volumetric estimation of possible Stafne bone concavities on cone beam computed tomography images. Oral Radiol 2020,36(3):254–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Minowa K, Inoue N, Izumiyama Y, et al. Static bone cavity of the mandible: Computed tomography findings with histopathologic correlation. Acta Radiol 2006;47(7):705–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Probst FA, Probst M, Maistreli IZ, Otto S, Troeltzsch M. Imaging characteristics of a Stafne bone cavity— panoramic radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;18(3):351–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Taysi M, Ozden C, Cankaya B, Olgac V, Yıldırım S. Stafne bone defect in the anterior mandible. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2014;43(7):20140075. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Lee JI, Kang SJ, Jeon SP, Sun H. Stafne bone cavity of the mandible. Arch Craniofac Surg 2016;17(3):162–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Hisatomi M, Munhoz L, Asaumi J, Arita ES. Parotid mandibular bone defect: A case report emphasizing imaging features in plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging Sci Dent 2017;47(4):269–73. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Krafft T, Eggert J, Karl M. A Stafne bone defect in the anterior mandible—A diagnostic dilemma. Quintessence Int 2010;41(5):391–3.

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Xianguang Liu - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Wenhui Xu - Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Xuxia Wang - Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2022 Xianguang Liu et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.