|

Case Report

Anti-resorptive related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient with hemodialysis: Rapid progression and pathologic fracture in a short phase

1 Assistant professor, DDS, PhD, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima, Japan

2 Research assistant, DDS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima, Japan

3 Research assistant, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima, Japan

4 Lecturer, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima, Japan

Address correspondence to:

Chihiro Kanno

1 Hikarigaoka, Fukushima City, Fukushima,

Japan

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100041Z07CK2022

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Kanno CK, Kitabatake T, Kojima M, Yamazaki M, Kaneko T. Anti-resorptive related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient with hemodialysis: Rapid progression and pathologic fracture in a short phase. J Case Rep Images Dent 2022;8(1):5–9.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Anti-resorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ) is a slowly progressive disease occurring due to the chronic use of antiresorptive agents (e.g., bisphosphonates) and rarely presents with pathologic fractures. The frequency of pathologic fractures is rare, especially in patients with osteoporosis who are prescribed, low-dose bone-modifying agents. Herein, we report a case of rapidly progressive ARONJ with a pathologic fracture in a patient with hemodialysis.

Case Report: A 64-year-old woman with hemodialysis due to the microscopic polyangiitis who was treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and ibandronate presented with tooth pain of left mandibular second premolar and second molar, necessitating extraction. After extraction, ARONJ developed in the left mandibular. Anti-resorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw progressed rapidly during the follow-up at the 12th and 15th months, furthermore, ARONJ also developed in the right mandibular second premolar and second molar lesion, requiring extensive surgery. We performed curative segmental and marginal mandibulectomy in the left and right hemimandible, respectively. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Conclusion: We report a rare case of rapidly progressive ARONJ with pathologic fracture in a patient with hemodialysis. This report suggests a potential role of hemodialysis as a risk factor for disease progression and pathologic fracture development. Further studies regarding factors that inhibit the healing of ARONJ are still needed.

Keywords: ARONJ, Hemodialysis, Low dose BMA, Pathologic fracture, Rapid progression

Introduction

Eighteen years since its discovery, anti-resorptive related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ), an adverse effect of anti-resorptive drugs with unclear pathophysiology and treatment, is still impairing the quality of life in many patients [1]. The incidence of ARONJ is lower in osteoporotic patients receiving low-dose bone modifying agents (BMA) than in those receiving high-dose BMA [2],[3]. Most ARONJ cases are chronic and progress slowly. To date, rapidly progressive ARONJ has been rarely reported. Herein, we report a case of rapidly progressive ARONJ with a pathologic fracture induced by low-dose BMA in a patient with hemodialysis.

Case Report

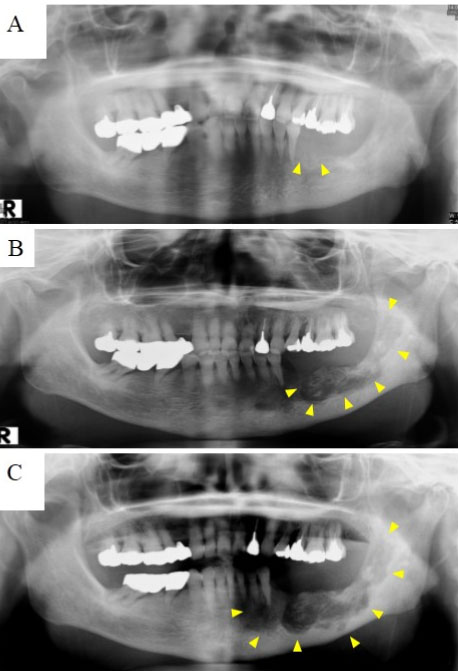

A 64-year-old postmenopausal woman was admitted for tooth pain. She underwent left mandibular second premolar and second molar extraction due to periodontitis. Four months after extraction, she was diagnosed with ARONJ stage 1 [4] at the extraction site (Figure 1A). At this point, she desired conservative therapy (i.e., oral hygiene and antibiotic therapy for acute inflammation), not curative surgical therapy. The course silently elapsed since diagnosis, however, during the period of 12- and 15-month follow-up, jaw pain and inflammation surrounding the left mandibular body worsened rapidly and panoramic radiography revealed a rapid spread of bone destruction, resulting in pathologic fracture of the left mandibular body (Figure 1B and Figure 1C), which prompted a referral to our clinic.

Four years before the consultation, she was diagnosed with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), which required hemodialysis, and had been treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and ibandronate. Physical examination revealed malocclusion, left inferior mandibular nerve paresthesia, and an extraoral fistula on submandibular skin. In the right mandibular second premolar and second molar region, exposed bone was detected in the periodontal pocket of these teeth. Radiologic examination revealed stage 3 and stage 1 ARONJ in the left and right hemimandible, respectively (Figure 2A, Figure 2B, Figure 2D, Figure 2C, Figure 2E). The causes of ARONJ were considered as tooth extraction in the left lesion and periodontitis in the right lesion. Approximately 17 months after first diagnosis, segmental and marginal mandibulectomy was performed in the left and right hemimandible, respectively. Mandibular reconstruction was not performed because of her poor health condition and difficulty in rigid fixation. The oral mucosa was sutured tightly for wound closure. Histopathologic examination of the resected bone showed bone necrosis with infiltration of inflammatory cells and Actinomyces granules (Figure 3A) in the absence of MPA. Twelve months after surgery, panoramic radiographs revealed that there was no recurrence of inflammation or bone destruction (Figure 3B). The postoperative course was uneventful. After 15 months of surgery, there were no findings of recurrence of inflammation.

Discussion

In the present case, ARONJ progressed rapidly during the follow-up at the 12th and 15th months, requiring extensive surgery. During the general course of ARONJ, patients receiving low-dose BMA have a slower progression of the disease than those receiving high-dose BMA. Furthermore, pathologic fractures develop only after a few years in patients receiving high-dose BMA, with an incidence rate of 2.9–4.3% [5],[6],[7]. However, to the best of our knowledge, in the English literature, only a few cases of pathologic fractures have been reported in patients treated with low-dose BMA [5],[6],[7],[8]. This study presented a case of ARONJ with pathologic fracture that worsened rapidly in the period of 12 to 15 months from diagnosis, nevertheless, the silent course was seen until then. This is considered extremely rare in a patient being treated with low-dose BMA.

In the present case, we hypothesized about the cause of rapid exacerbation, first, the role of hemodialysis is considered as a potential factor. During wound healing, hemodialysis is strongly related to poor healing. Patients with hemodialysis have a higher tendency of wound infection and wound dehiscence [9],[10]. The factors related to inhibition of wound healing in patients with hemodialysis are arteriosclerosis, impaired peripheral blood flow, and reduced immunity. Additionally, use of corticosteroid and the impairment of calcium metabolism due to renal dysfunction might concerned. Impaired calcium concentration results in low bone density and fragility of bone. In contrast, in the development of ARONJ, hemodialysis is defined as a risk factor in many guidelines of ARONJ; however, it is not stated as a healing inhibitor. Moreover, resolution of bacterial infection, necrotic bone separation, and epithelization are the crucial factors in ARONJ healing; thus, correlation with hemodialysis may be hypothesized.

Next, the role of MPA is considered. MPA is a systemic disease that causes necrotizing vasculitis of the small and medium blood vessels [11], and occurs multi-organ dysfunction in whole body especially in the kidneys, lungs, skin, and ears. Nevertheless, long-term treatment with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants is crucial for its management [12],[13],[14], little progress has been made with multiple comorbidities. The histopathological feature of necrotic vasculitis is distinctive in MPA. According to the pathophysiology of MPA, the course of this atypical case could be explained. However, in the present case, it was difficult to evaluate MPA histopathologically, because in the resected sample was just necrotic bone, not the healthy bone. Although the distinctive histopathological feature is not often observed in the target organs [11], whether MPA exacerbates ARONJ is unclear.

In ARONJ treatment outcome, curative surgical therapy, such as necrotic bone removement, with surrounding healthy region is expected to have a better outcome compared to conservative therapy. As the first choice of ARONJ treatment, conservative therapy is recommended in some guidelines [4],[15],[16]. On the other hand, the efficacy of surgical therapy has been reported [17] [18]; however, it is still controversial. In the present case, the clinical course was rapidly exacerbated in a short term during the conservative therapy, consequently, extensive surgery was performed. Our patient exhibited two factors that were related to wound healing complications, both the factors had the possibility of causing inhibition of healing in ARONJ, though it is unclear. In light of this case, surgical therapy should be considered in the early clinical stage in ARONJ with several healing inhibiting factors, such as hemodialysis or MPA, to avoid rapid exacerbation and extensive surgery to provide a better quality of life to the patients.

Conclusion

We reported a case of rapidly progressive ARONJ with a pathologic fracture in a patient with hemodialysis. This study suggests a potential role of hemodialysis as a risk factor for disease progression and pathologic fracture development in ARONJ. Nevertheless, further research is still required to determine the exact role of hemodialysis in patients with ARONJ.

REFERENCE

1.

Marx RE, Cillo JE Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: Risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65(12):2397–410. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Veszelyné Kotán E, Bartha-Lieb T, Parisek Z, Meskó A, Vaszilkó M, Hankó B. Database analysis of the risk factors of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in Hungarian patients. BMJ Open 2019;9(5):e025600. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and international consensus. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30(1):3–23. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw; Yoneda T, Hagino H, et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position Paper 2017 of the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J Bone Miner Metab 2017;35(1):6–19. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Topaloglu Yasan G, Adiloglu S, Koseoglu OT. Retrospective evaluation of pathologic fractures in medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2021;49(6):518–25. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Grana J, Mahia IV, Sanchez Meizoso MO, Vazquez T. Multiple osteonecrosis of the jaw, oral bisphosphonate therapy and refractory rheumatoid arthritis (Pathological fracture associated with ONJ and BP use for osteoporosis). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26(2):384–5.

[Pubmed]

7.

Yao M, Shimo T, Ono Y, Obata K, Yoshioka N, Sasaki A. Successful treatment of osteonecrosis-induced fractured mandible with teriparatide therapy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;21:151–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Jowett A, Abdullakutty A, Bailey M. Pathological fracture of the coronoid process secondary to medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;10:162–5. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Cheung AH, Wong LM. Surgical infections in patients with chronic renal failure. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2001;15(3):775–96. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Bihorac A, Delano MJ, Schold JD, et al. Incidence, clinical predictors, genomics, and outcome of acute kidney injury among trauma patients. Ann Surg 2010;252(1):158–65. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Samman KN, Ross C, Pagnoux C, Makhzoum JP. Update in the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis: Recent developments and future perspectives. Int J Rheumatol 2021;2021:5534851. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Suwanchote S, Rachayon M, Rodsaward P, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and their clinical significance. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37(4):875–84. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Almaani S, Fussner LA, Brodsky S, Meara AS, Jayne D. ANCA-associated vasculitis: An update. J Clin Med 2021;10(7):1446. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Yarom N, Shapiro CL, Peterson DE, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: MASCC/ISOO/ASCO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2019;37(25):2270–90. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;72(10):1938–56. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Hayashida S, Soutome S, Yanamoto S, et al. Evaluation of the treatment strategies for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) and the factors affecting treatment outcome: A multicenter retrospective study with propensity score matching analysis. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32(10):2022–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Hoefert S, Yuan A, Munz A, Grimm M, Elayouti A, Reinert S. Clinical course and therapeutic outcomes of operatively and non-operatively managed patients with denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (DRONJ). J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017;45(4):570–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Chihiro Kanno - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Takehiro Kitabatake - Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Momoyo Kojima - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Morio Yamazaki - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Tetsuharu Kaneko - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Editage (www.editage.co.jp) for English editing service.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2022 Chihiro Kanno et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.