|

Case Report

Usage of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes for closure of soft palate recurrent fistula

1 Director, Post-Graduation Program of Oral Implantology, Instituto Cearense de Ensino Odontológico (ICEO), Fortaleza, Brazil; Private Practice in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil

2 Dentistry and Research, Research Center in Morphology and Applied Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Brasília, Brazil

3 Research and Student, Pos-Graduate Program in Oral Implantology, Prosthodontics and Periodontology, Instituto de Cearense de Ensino Odontológico (ICEO) Fortaleza, Brazil; Private Practice in Dental Implants, Dental Prosthesis and Periodontology in Assaré, Ceará, Brazil

Address correspondence to:

Jaqueline Alves do Nascimento

Street Pe. Valdevino 276, Fortaleza, Ceará, Zip Code: 60135-041,

Brazil

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100042Z07SQ2022

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

de Queiroz SBF, de Oliveira LA, do Nascimento JA. Usage of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes for closure of soft palate recurrent fistula. J Case Rep Images Dent 2022;8(1):10–13.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Palatal fistula is a relatively common complication of surgical procedures to treat congenital or acquired conditions on the hard or soft palate. Its treatment is associated with high recurrence rates. Blood extracts passed by centrifugation are being commonly used for the stimulation of palatal cells for tissue regeneration, promoting faster healing.

Case Report: This case report is to describe the case in which platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membranes were used to close the palatal fistula after flap necrosis.

Conclusion: Among the usual blood extracts, PRF has been shown to be effective for adjuvant treatment of palatal fistula healing.

Keywords: Palatal fistula, PRF, Recurrence, Surgery

Introduction

Palatal fistula is a relatively common complication from surgical procedures to treat congenital or acquired conditions in the hard or soft palate. This condition is most associated with cleft palate surgery, but other palatal interventions can also lead to this sequel [1],[2]. Fistula of the palate can cause extreme discomfort, and the most common symptoms are food and liquids passage through the nasal cavity. Escape of air during speech can result in hypernasality [1],[3],[4].

Treatment o of palatal fistulas is technically challenging, and different techniques are described in the literature, including local and regional flaps, tissue grafts, pedicle flaps, and obturator prosthesis [3],[5]. The choice of a specific technique depends on factors such as location, size of the fistula, and patient age [2]. Early failure and recurrence can occur and may be related to closure under tension of the flap and poor surgical technique, leading to flap necrosis and dehiscence [1].

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is an autologous blood concentrate with applications in tissue repair. It acts as a three-dimensional histogenic continuum impregnated with angiogenic growth factors [6]. Platelet-rich fibrin is obtained in a closed sterile system for selective fractionation in low-speed centrifugation, where it can be obtained quickly and at a low cost [7]. We report a case in which we used PRF matrices to close a palatine fistula after flap failure.

Case Report

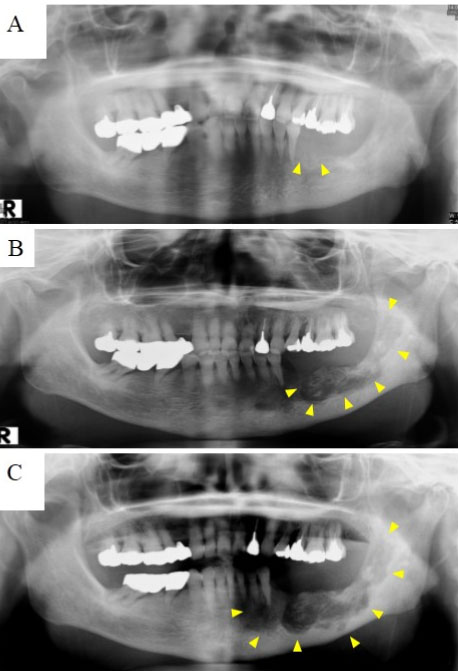

A 45-year-old woman presented at our clinic with history of benign salivary gland tumor resection in the left posterior palate five years ago. After healing, a fistula of 5 mm was present on the left side of the soft palate (Figure 1). The patient reported regurgitation of food and liquids to the nasal cavity and slight hypernasality was present. No previous surgical attempt to close the fistula was made. After an accurate hematological examination, the patient was found to be normosystemic, with all preoperative tests within normal limits. We decided to do the closure of the fistula under general anesthesia, using a modified von Langenbeck technique, achieving a two layer (nasal and oral) closure (Figure 2). The patient had a surgery three years before the pandemic COVID-19.

Healing was uneventful in the first days, but around day 10, we noticed partial flap necrosis and dehiscence, with reopening of oronasal communication around two weeks (Figure 3). Thus, we decided to use PRF membranes to fill the wound. We also sutured the fibrin membranes to the edges of both nasal and oral flap with a slight approximation of the wound edges with loose sutures (Figure 4).

The procedure was done under local anesthesia. The PRF membranes were obtained collecting peripheral blood from antecubital fossa in 10 mL glass tubes without additives (8 tubes, 80 mL in total) and immediately centrifuged (400 g/10 minutes/2000 rotations). The fibrin clots obtained were removed from the tubes, placed in the PRF box, and pressed, obtaining the PRF membranes that were used to fill the defect. After one week, it was possible to see granulation tissue over the wound and with two weeks, the membranes were almost totally degraded, but still partially filling the wound, with no signs of oronasal communication (Figure 5). After three months, the mucosa was fully healed and without signs of recurrence of the fistula (Figure 6).

Discussion

Closure of palatal fistulas is associated with high recurrence rates [1]. The repair of such fistulas is challenging due to restricted surgical access, limited availability of local tissue, scarring from previous surgery, and poor blood supply. Two-layered closure provides greater support and stability and reduces the risk of failure [2]. In our case report, no previous attempts to close the fistula were made before. Due to the size of the fistula and the presence of food/liquid regurgitation presented by the patient, we opted to perform the two-layer closure to isolate the nasal and oral cavities. Unfortunately, the early flap failure led to the fistula relapse.

As an attempt to salvage the flap, we decided to fill the defect with PRF membranes. Platelet-rich fibrin has been used in a variety of clinical situations involving the healing soft and hard tissue defects, including very challenging clinical situations, such as refractory leg ulcers 20 and mucosal defects in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws [7],[8],[9]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that PRF matrices interact with adjacent tissue as a temporary and surrogate means of continuity. Platelet-rich fibrin plays an antiproteolytic role that keeps growth factors adhered to and protected, enhancing the healing process by stimulating cell proliferation, fibroplasia, and angiogenesis [6],[7],[10],[11]. Furthermore, PRF matrices remain intact for more than seven days in vitro and 28 days in culture, undergoing slow fibrinolysis [10],[11]. We have been using PRF routinely in many clinical situations for over eight years, with mostly positive results. Thus, we believe it may be beneficial, especially in healing soft tissue injuries.

Conclusion

In conclusion, palatal fistulas require a treatment plan that includes nutrition with differentiated cell proliferation for tissue regeneration and closure. The PRF proved to be very effective for tissue repair and fistula closure in a fast and safe way.

REFERENCE

1.

Strujak G, de Lima do Nascimento TC, Biron C, Romanowski M, de Lima AAS, Carlini JL. Pedicle tongue flap for palatal fistula closure. J Craniofac Surg 2016;27(8):2146–8.

[Pubmed]

2.

Sahoo NK, Desai AP, Roy ID, Kulkarni V. Oro-nasal communication. J Craniofac Surg 2016;27(6):e529–33.

[Pubmed]

3.

Abdel-Aziz M, El-Hoshy H, Naguib N, Reda R. Furlow technique for treatment of soft palate fistula. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012;76(1):52–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Ohno T, Hojo K, Fujishima I. Soft obturator prosthesis for postoperative soft palate carcinoma: A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2018;119(5):845–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Prakash A, Singh S, Solanki S, et al. Tongue flap as salvage procedure for recurrent and large palatal fistula after cleft palate repair. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2018;15(2):88–92. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;101(3):e37–44. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Pinto NR, Ubilla M, Zamora Y, Del Rio V, Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Quirynen M. Leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) as a regenerative medicine strategy for the treatment of refractory leg ulcers: A prospective cohort study. Platelets 2018;29(5):468–75. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Somani A, Rai R. Comparison of efficacy of autologous platelet-rich fibrin versus saline dressing in chronic venous leg ulcers: A randomised controlled trial. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2017;10(1):8–12. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Szentpeteri S, Schmidt L, Restar L, Csaki G, Szabo G, Vaszilko M. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin membrane in surgical therapy of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;78(5):738–48. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Diss A, Odin G, Doglioli P, Hippolyte MP, Charrier JB. In vitro effects of Choukroun’s PRF (platelet-rich fibrin) on human gingival fibroblasts, dermal prekeratinocytes, preadipocytes, and maxillofacial osteoblasts in primary cultures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;108(3):341–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

de Oliveira LA, Borges TK, Soares RO, Buzzi M, Kückelhaus SAS. Methodological variations affect the release of VEGF in vitro and fibrinolysis’ time from platelet concentrates. PLoS One 2020;15(10):e0240134. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Sormani Bento Fernandes de Queiroz - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Leonel Alves de Oliveira - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Jaqueline Alves do Nascimento - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2022 Sormani Bento Fernandes de Queiroz et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.