|

Case Report

Endodontic management of a multi-rooted tooth as a foundation dentist

1 General Dentist, Temple Street Dental Practice, Oxford, United Kingdom

Address correspondence to:

Ayla Arif Mahmud

Temple Street Dental Practice, 26 Temple Street, Oxford, OX4 1JS,

United Kingdom

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100048Z07AM2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Mahmud AA. Endodontic management of a multi-rooted tooth as a foundation dentist. J Case Rep Images Dent 2025;11(1):1–5.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Dental caries is a multifactorial disease, caused by demineralization of hard tissue as a result of acids produced due to fermentation of carbohydrates. It is the most prevalent chronic disease globally, with a prevalence of 36% in the global adult population. Streptococcus mutans, an acidogenic bacterial species, is considered to be the predominant causal agent. If dental caries progresses into the pulp chamber of the tooth, direct pulp capping or root canal treatment (RCT) may be indicated. Root canal treatment is performed to manage infection caused by the ingress of bacteria. The aim of RCT is to reduce the bacterial load in the root canal system by chemo-mechanical debridement and the root canals are prepared to maximize irrigant penetration.

Case Report: This case report demonstrates structured evidence-based approach to management of a multi-rooted maxillary first molar (UR6) by a foundation dentist in a general practice setting. The patient presented with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis of the UR6 and opted for RCT of the tooth, followed by cuspal coverage with a metal onlay.

Conclusion: This case discusses the considerations and step-by-step management of endodontic treatment to achieve a successful outcome. It highlights the importance of understanding root canal anatomy and employing tools such as magnification and ultrasonics, in addition to maintaining clear communication with patients about their treatment options. Reflection on cases such as these aids professional growth and fosters an understanding of the decision-making process.

Keywords: Dentistry, Endodontics, Practice, Multi-rooted

Introduction

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease, caused by demineralization of hard tissue as a result of acids produced due to fermentation of carbohydrates [1]. It is the most prevalent chronic disease globally, with a prevalence of 36% in the global adult population [2]. Streptococcus mutans, an acidogenic bacterial species, is considered to be the predominant causal agent [3]. If dental caries progresses into the pulp chamber of the tooth, direct pulp capping or root canal treatment (RCT) may be indicated.

Root canal treatment is performed to treat infection caused by the ingress of bacteria in the root canal system [4]. The aim of RCT is to reduce the bacterial load in the root canal system by chemo-mechanical debridement and maximize penetration of the irrigant [5]. The root canal system is sealed to prevent the ingress of further bacteria. Thus, it allows for healing, pain relief, and maintenance of tooth function.

This case report discusses the treatment journey of Patient X and the stages and considerations taken in completing RCT of the upper right first molar (UR6). The UR6 typically has 3 roots. Increasingly, studies have shown a steady increase in the percentage of mesiobuccal roots having 2 canals, with in vivo studies stating up to 73% of teeth containing a second mesiobuccal canal [6]. Successful RCT is achieved resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and evidence of healing radiographically [7].

Most commonly RCT fails due to persistence of infection in the root canal system or periradicular space. In cases with more complex anatomy, chemo-mechanical disinfection of the root canal system is more challenging. Studies have shown this to be particularly difficult in the apical portion of the tooth [8]. This emphasizes the importance of careful and thorough chemo-mechanical preparation of teeth during endodontic treatment.

Case Report

History and examination

This patient presented to general practice with pain from his UR6 which was “painful to bite down” and “very sensitive to cold.” A pain history was taken busing the SOCRETES (site, onset, character, radiation, associated symptoms, time, exacerbating and reliving factors, and severity) acronym. The patient reported that the pain was well localized to the UR6. It had developed one month prior and had progressively worsened. He was experiencing a continuous dull ache, radiating to his temple which was resulting in a headache. Paracetamol provided mild relief, and the patient reported an overall severity of 7/10.

The patient was medically fit and well, with no known allergies, and a regular dental attender with a moderately restored dentition and moderate tooth wear due to a parafunctional habit. Diet analysis showed a low cariogenic diet. The patient had good oral hygiene, using an electric toothbrush 2×/day with a fluoride toothpaste and presented with plaque scores <20%. The basic periodontal examination (BPE) was 111/121. The patient was a non-smoker and did not consume alcohol.

No extra-oral or intra-oral soft tissue abnormalities were detected. Endodontic assessment evidenced the tooth was restorable. An amalgam filling had been placed five years earlier. There was no a sinus tract or buccal swelling/tenderness. The tooth was tender to percussion and hyperresponsive to Endofrost cold test. There were no pockets greater than 3.5 mm circumferentially and the tooth was not mobile.

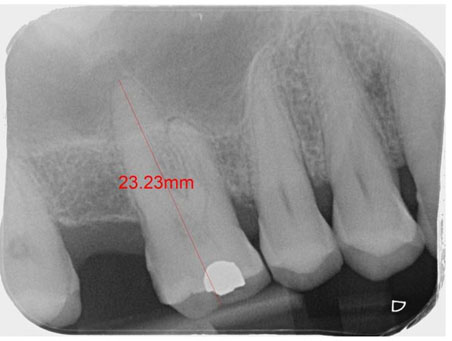

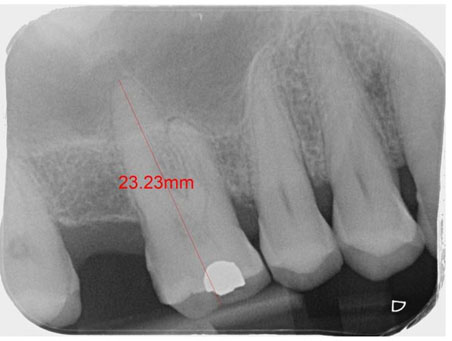

Radiographic examination using a periapical radiograph (Figure 1) showed an occlusal restoration, widening of the periodontal ligament (PDL) and a small apical radiolucency of the mesial root, with approximately 30% horizontal bone loss.

Methodology

Following taking a through patient history and examination, a diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis was determined. The findings and treatment options were discussed with the patient including no treatment, RCT, and extraction. Following a conversation regarding prognosis, risks and benefits, and treatment with a specialist/dentist with special interest options, the patient opted to have root canal treatment carried out by a general dentist.

The acute phase of the treatment plan involved extirpation of the UR6 to relive symptoms. The next step was to ensure that the patient was dentally stable, for improved outcomes of treatment. This included delivery of oral hygiene instructions, diet advice, and professional mechanical plaque removal. Once the patient was stabilized, RCT of the UR6 was initiated with the view of providing cuspal coverage following completion of treatment.

Treatment was commenced under rubber dam using single tooth isolation. The tooth was accessed, and 3 canals were identified using a DG16 probe under magnification. The canals were irrigated with sodium hypochlorite and the tooth was temporized with non-setting calcium hydroxide.

At the following appointment, an estimated working length was calculated using computer software. The apical constriction is estimated to be 1 mm from this length. The access cavity was refined to give unimpeded access and visualization of the root canal system (Figure 2). The estimated working lengths were verified using an apex locator following preparation of the coronal 2/3 with Gates-Glidden and a working length radiograph was taken to confirm the lengths (Figure 3). Glyde lubricant gel was used on the files which contains 19% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, a chelating agent that binds to calcium and removes the inorganic debris. This aids irrigant penetration, however, reacts with hypochlorite forming a precipitate so should be used sparingly.

Using a crown-down method, the canals were coronally flared to two-thirds of the length using Gates-Glidden drills, cutting on the outward stroke. This cleared the coronal two-thirds, which contains the highest bacterial load, preventing facilitation of the progression of the bacteria into the apical portion. This also improved access for irrigant and reduced the curvature, reducing the chance on file separation. Between each instrument, a size 10 file was used to maintain patency. A 27 gauge side venting syringe was used to passively deliver 1% sodium hypochlorite for lubrication and its bactericidal properties.

The apical portion of the canal was prepared up to the working length with K files, using the balanced force technique. Copious irrigation and lubricant was used between instruments. Using the step-back technique with consecutively larger files and reducing the length by 1 mm each time, flaring was achieved.

The canal was dried using paper points and a master apical point radiograph was taken (Figure 4). This radiograph showed that the palatal gutta percha (GP) point was 2 mm short of the apex, so further canal preparation was conducted. Using the cold lateral technique, the canals were obturated with GP, using a zinc oxide eugenol-based sealant. Using finger spreaders, accessory points were added following lateral condensation to ensure the canal was fully obturated. Excess GP was cut and packed using an endodontic plugger to achieve an impermeable, fluid tight seal. Using Gate-Glidden burs, the coronal GP was removed to place an Nayyar core for fracture resistance and a final radiograph was taken (Figure 5).

Discussion

Prognosis depends on the quality of canal preparation for irrigant penetration, obturation, and a good coronal seal [9]. Signs of success include boney infill in successive radiographs following RCT and the absence of pain. The RCT post-operative radiograph shows a good taper and the GP was well condensed. The length of the root canal obturation was within 1 mm of the apex [10]. Patency was achieved throughout the procedure and the patient returned at the time of obturation the symptoms had resolved

In this case, only one mesiobuccal canal was located. A cross-sectional study showed that of a sample of 20,836 endodontically treated teeth with periapical lesions, 82.6% were associated with missed canals [11]. The use of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) 3D scan is being increasingly used routinely for pre-operative endodontic assessment. A study assessing the prevalence of a second mesiobuccal canal in maxillary molars showed that while practitioners had identified only one mesiobuccal canal in 70% of patients, CBCT volumes visualized that 86% of maxillary first molars had a second mesiobuccal canal [12]. Therefore, it is important to consider the use of CBCT scan to ensure that there is not an untreated mesiobuccal canal.

Treatment could also be improved by using an endodontic activator for sonic irrigation with recent studies having showed a statistically significant lower smear layer than ultrasonic irrigation, thus resulting in improved cohesion between sealer and dentinal tubules which results in reduced chance of bacterial ingress [13]. This would also improve irrigation of lateral canals which may be present, further reducing the bacterial load.

Cuspal coverage of posterior teeth is advised as the tooth is weakened following root treatment, thus more prone to fracture [14]. The tooth was restored with a well-sealed metal onlay. The cuspal coverage prevents cuspal flexion, which could facilitate ingress of bacteria. This is especially important for patient X who had a parafunctional habit. The patient was placed on a 6-month check-up recall as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, at which point the root-treated tooth remained asymptomatic [15].

Conclusion

This case report demonstrates structured evidence-based approach to management of a multi-rooted tooth by a foundation dentist in a general practice setting. It discusses the considerations and step-by-step management of endodontic treatment to achieve a successful outcome.

It highlights the importance of understanding root canal anatomy and employing tools such as magnification and ultrasonics, in addition to maintaining clear communication with patients about their treatment options. Reflection on cases such as these aids professional growth and fosters an understanding of decision making.

As technologies have developed, we are able to take CBCT with relatively low radiation doses, to have a deeper understanding of the tooth anatomy. It is also essential to recognize the importance of long-term restoration with cuspal coverage to increase longevity of the tooth.

REFERENCE

1.

2.

Yadav K, Prakash S. Dental caries: A microbiological approach. J Clin Infect Dis Pract 2017;2(1):118. [CrossRef]

3.

Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis – A comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44 Suppl 18:S94–105. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

European Society of Endodontology. Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: Consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int Endod J 2006;39(12):921–30. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Murray CA, Saunders WP. Root canal treatment and general health: A review of the literature. Int Endod J 2000;33(1):1–18. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Stropko JJ. Canal morphology of maxillary molars: Clinical observations of canal configurations. J Endod 1999;25(6):446–50. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Estrela C, Holland R, de Araújo Estrela CR, Alencar AHG, Sousa-Neto MD, Pécora JD. Characterization of successful root canal treatment. Braz Dent J 2014;25(1):3–11. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Siqueira JF Jr. Aetiology of root canal treatment failure: Why well-treated teeth can fail. Int Endod J 2001;34(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

10.

Dummer PM, McGinn JH, Rees DG. The position and topography of the apical canal constriction and apical foramen. Int Endod J 1984;17(4):192–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Baruwa AO, Martins JNR, Meirinhos J, et al. The influence of missed canals on the prevalence of periapical lesions in endodontically treated teeth: A cross-sectional study. J Endod 2020;46(1):34–9.e1. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Parker J, Mol A, Rivera EM, Tawil P. CBCT uses in clinical endodontics: The effect of CBCT on the ability to locate MB2 canals in maxillary molars. Int Endod J 2017;50(12):1109–15. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Paixão S, Rodrigues C, Grenho L, Fernandes MH. Efficacy of sonic and ultrasonic activation during endodontic treatment: A meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Acta Odontol Scand 2022;80(8):588–95. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Patil AM, Deshpande S, Ratnakar P, Patil V, Surabhi R, Reza KM. To evaluate the fracture resistance of four core buildup materials: Amalgam, resin composite/dual cure, resin-modified glass ionomer, and SureFil packable composite restorative material under universal testing machine. International Journal of Oral Care and Research 2020;8(1):5–7 [CrossRef]

15.

Clarkson JE, Amaechi BT, Ngo H, Bonetti D. Recall, reassessment and monitoring. Monogr Oral Sci 2009;21:188–98. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Ayla Arif Mahmud - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthor declares no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Ayla Arif Mahmud. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.